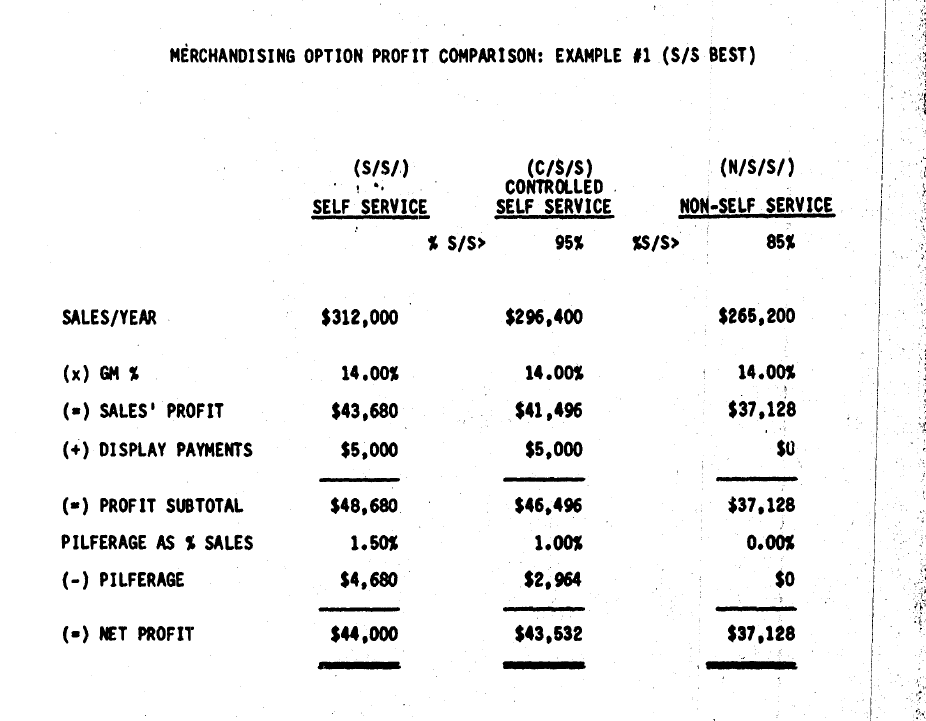

In September, 1985 ,R. J. Reynolds created a sales presentation about shoplifting called “Pilferage in Perspective,” to try and talk retailers out of the “knee jerk reaction” of moving their cigarettes out of reach of customers in response to high rates of pilferage. The document shows how, in most cases, retailers could make a bigger profit if they let their cigarettes be stolen, due to the industry-paid “placement,” “merchandising” or “slotting fees.” Tobacco companies paid these fees, which were often sizable, to retailers in exchange for placing self-service cigarette displays in specific locations in stores like in front of the cash register, below counter level or adjacent to displays containing candy and toys. The displays were often required to be kept in locations that made it difficult for clerks to oversee them and limit shoplifting from them. Many clerks expressed profound frustration with the arrangement, since they were often held responsible for stolen merchandise. The RJR document contains equations that demonstrate for retailers how their slotting fees more than offset their loss from theft. Note the example at the end of the document, which cites the average Winn Dixie grocery store selling 450 cartons a month. RJR explains that this Winn-Dixie store can actually make a higher profit from tobacco if the owner accepts up to a 6 percent pilferage rate along with their slotting fees. A 6 percent pilferage rate at the stated quantity of monthly sales means the store’s average loss would be 5,400 cigarettes every week, or almost 290,000 cigarettes each year, from a single grocery store. Why would cigarette companies encourage theft of their products? Because it gets cigarettes into the hands of children, cigarettes are addictive, and the return on the cigarette companies’ investment is huge. If just half of the stolen cigarettes get into the hands of kids who smoke ten cigarettes each, and just one quarter of those kids went on to become regular smokers, then the pilferage occurring at this single Winn Dixie store would recruit over 3,000 new smokers each year. At an average smoking rate of 1 1/2 packs a day, in 1997 each new smoker would have generated about $36,000 for tobacco companies over his or her lifetime. This group of kids in aggregate would generate hundreds of millions of dollars for the industry before they quit or die, all from just one store. This largely hidden, pay-for-theft financial arrangement made cigarettes the single most shoplifted item in the country throughout the late 1980s and most of the 1990s. According to the Food Marketing Institute, in 1997 cigarettes accounted for 41 percent of all shoplifted items nationwide, and were the single most shoplifted item from stores across the U.S. In addition, a 1993 survey of 60,000 children by the Pennsylvania Department of Health found that 47 percent of children from the 7th to the 12th grade admitting to getting most of their cigarettes from shoplifting. Once people discovered huge quantities of cigarettes were routinely being shoplifted and that it was facilitated by this pay-for-placement scheme, people started demanding that cigarettes be kept locked up or behind counters. Since then, public health advocates succeeded in getting many states to pass laws banning self-service cigarette displays. Now cigarettes are the most frequently locked-up item in stores, with about 62 percent of all stores locking them up. As a result, cigarettes now account for just 2.1 percent of all shoplifted items nationwide, a big improvement, and no doubt countless kids are being saved from a lifetime of nicotine addiction.

Source/Cited document: Pilferage Presentation: Core Presentation., sales presentation, R.J. Reynolds, September 12, 1985, Bates No. 514348983/9015 (33 pages)

Sinister. As usual with drug pushers.