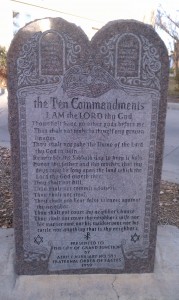

Grand Junction’s Ten Commandments tablet, donated in 1959 by the Fraternal Order of Eagles, which only admits people who believe in God.

Anyone who thinks that electing narrow-minded people to city councils in small American towns doesn’t get expensive, think again. The parochial minds of just five elected city council members in the town of Grand Junction, Colorado cost city taxpayers $64,000 and led to the creation of a big, permanent public reminder on City Hall grounds of how they spent that huge sum to evade the law and collectively thumb their nose at the U.S. Constitution.

It all started in 1959, when the City of Grand Junction accepted a gift from the Fraternal Order of Eagles (FOE), a do-good civic group that restricts its membership only to people who believe in God. The gift was a stone tablet engraved with the Ten Commandments, a religious symbol commanding people to worship God, which City officials installed on City Hall grounds. There it sat, little-noticed, for the next fifty years, its presence often obscured by mature landscaping. All that changed in 2000, when the City put the finishing touches on construction of a new City Hall building and relocated the Ten Commandments to a much more visible location on the grounds.

The tablet’s more prominent location made it more noticeable, and some local citizens also finally happened to notice the Constitutional violation it represented. As a result, in April, 2001 five local citizens and the American Civil Liberties Union sued the City over the monument, asking them to remove it because it made members of minority religious groups, nonbelievers and community political outsiders feel unwelcome. The plaintiffs also contended it represented a government establishment of religion.

Many Grand Junction Christians weighed in with Council, pressing them to dig in their heels for the Lord, resist pressure and keep the tablet at any cost. A nearby church offered to help the City out of its jam by relocating the tablet to the church’s grounds, where they would host it for free, on a busy City corner — a simple, inexpensive and almost instantaneous solution. But Council would have none of that. Instead, in March of 2001, Council voted 5-2 to keep the granite tablet and do everything it possibly could to shake off the lawsuit over the monument. The two council members who voted to send the monument to the church were then-Mayor Gene Kinsey and council member Jim Spehar. They opposed keeping the tablet at city hall because they were afraid the City would lose the threatened legal challenge. City Attorney Dan Wilson had advised council that such a suit would cost in the range of six figures, take over two years to resolve and that the City would likely lose.

Grand Junction’s $64,000 “Cornerstones of Law and Liberty Plaza,” (a.k.a. “The Graveyard in Front of City Hall”), a reminder of how the City acted to avoid having to comply with the separation of church and state embodied in the U.S. Constitution.

Mayor Kinsey, commenting on his choice to take the church up on its offer, said, “I may not agree with the laws, but I am sworn as a council member to uphold them” — a sensible statement from a thoughtful leader who wanted to do what was best for the City. But the rest of Council instead looked around desperately for a way to avoid the lawsuit without having to comply with the First Amendment. They stole an idea from Bannock County, Idaho which had successfully dodged a 1993 lawsuit over a FOE Ten Commandments tablet on taxpayer-funded, county land by adding a disclaimer near the monument that read,

“This display is not meant to endorse any particular system of religious belief. As Thomas Jefferson stated, our democracy is premised upon the belief that government should not intrude into matters of religious worship. Still, as a historical precedent, the Ten Commandments represent some of man’s earliest efforts to live by the rule of law. Many of these ancient pronouncements survive in our jurisprudence today.”

For good measure, Bannock County also threw in the text of Virginia’s Statute of Religious Freedom, written by Thomas Jefferson. Bannock County officials then testified in court that the real purpose of having the Ten Commandments on county property was not religious at all, but to “memorialize the rule of law.” Placing the Ten Commandments in this historical context and being disingenuous in court testimony ultimately paid off with the dismissal of the lawsuit against the county.

Grand Junction City Council, upon hearing of this success in Bannock County, immediately adorned their Ten Commandments with a similar disclaimer saying their display “is not meant to endorse any particular system of religious belief.” Councilmembers hired a local landscape architect to design a “Cornerstones of Law and Liberty” plaza to bolster their last-minute effort to put the Ten Commandments into a contrived “historical context.” Alongside its coveted Ten Commandments, for good measure Council also threw in engraved granite tablets of the Magna Carta, the Mayflower Compact, the Declaration of Independence, the preamble to the Constitution and the preamble to the Bill of Rights.

Reford Theobold, the Grand Junction City Council member who led the $64,000 end-run around the U.S. Constitution.

Council’s “Plaza” cost Grand Junction taxpayers a whopping $64,000, and it did effectively end the lawsuit. Reford Theobold, the councilor who led the charge to avoid having to comply with the Constitution and who doggedly pursued the contrived $64,000 solution instead of agreeing to relocate the tablet to the nearby church, became a local hero. The City later named a newly-constructed pressbox at the local publicly-owned ballpark after Theobold. For his vote to make an honest effort to comply with the U.S. Constitution at no cost to taxpayers by sending the tablet to the nearby church, Kinsey was voted out of office in the next election. The “Cornerstones of Law and Liberty” Plaza remains in front of the Grand Junction City Hall, prompting tourists to ask why there is a “graveyard” in front of City Hall. The answer is because it represents the death of true patriotism in Grand Junction. The “graveyard” serves as a continuing reminder of the City of Grand Junction’s flagrant end-run around the Constitution, and of how the City put its thumb in the eye of every local citizen who seeks to be treated equally under the law and who knows the shameful history of how the “Plaza” came to be.

5 comments for “The City of Grand Junction, Colorado’s Shameful End-Run Around the Constitution”