A midwife in Vernal, Utah, has raised a red flag about a spike in the number of stillbirths and neonatal deaths in the small town in 2013. The statistic has emerged alongside explosive growth in drilling and fracking in the area. Energy companies have flocked to Vernal in the last few years to develop the massive oil and gas fields that underlie Uintah County.

The midwife, Donna Young, who has worked in the Vernal area for 19 years, reported delivering the first stillborn baby she’s seen in all her years of practice in May, 2013. Doctors could not determine any reason for the baby’s death.

While visiting the local cemetery where the parents of that baby had buried their dead child, Young noticed other fresh graves of babies who were stillborn or died shortly after birth.

Young started researching local sources of data on stillbirths and neonatal deaths, like obituaries and mortuary records, and found a large spike in the number of infant deaths occurring in Vernal in recent years. She found 11 other incidents in 2013 where Vernal mothers had given birth to stillborn babies, or whose babies died within a few days of being born.

Vernal’s full-time population is only about 9,800.

The rate of neonatal deaths in Vernal has climbed from about equivalent to the national average in 2010, to six times the national average in 2013.

Along with the surge in oil and gas drilling in the Vernal area over the last few years, the winter time air in the Uintah basin, where Vernal sits, has become dense with industrial smog generated by drilling rigs, pipelines, wells and increased traffic.

Drilling Industry Blocked a Previous Proposed Study of Air Quality in Vernal

Vernal’s deteriorating air quality has been a problem for years.

In 2007, a drilling industry group called the Western Energy Alliance, formerly the Petroleum Association of Mountain States, succeeded in killing a proposal by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) to study the effects of thousands of new oil and gas wells on air pollution in the Vernal area. Industry documents show that Bill Stringer, the head of BLM’s Vernal office, pushed to have an industry-controlled study substituted for the BLM study. The industry released it’s study in 2009. It concluded, not unexpectedly, that drilling had “no unacceptable effects on human health” in the Vernal area.

Stringer’s industry-friendly Vernal BLM office went on to approve an average of 555 new oil and gas wells in the Vernal area each year.

By early 2010, air monitors in the Vernal area started registering ozone levels among the worst in the country, on par with Los Angeles.

In 2012, a coalition of conservation and public health groups sued the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency for failing to protect the air quality in the Uintah Basin.

Citizens Skeptical About State Study’s Design

Utah’s state Department of Health said it will foot the bill to study the spike in neonatal deaths in Vernal, but area residents are skeptical the state may use outdated statistics or otherwise design the study to fail amid political pressure to abandon the research.

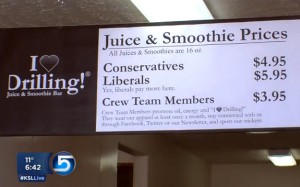

The “I Love Drilling” Juice Bar in Vernal, Utah, offers different prices to customers based on whether they are liberals, conservatives or work in the drilling industry.

Utah is one of the most drilling-friendly states in the union. Vernal, Utah’s drilling epicenter, is even home to the oddly-named “I Love Drilling” Juice and Smoothie Bar, which offers customers different prices based on whether they are politically liberal or conservative, or work in the drilling industry (the lowest price).

A similar situation with a questionable health department study occurred in nearby Garfield County, Colorado in April, 2014, after the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment (CDPHE) said it would conduct a similar study on an abnormally high rate of fetal abnormalities found in heavily-drilled Garfield County, on Colorado’s western slope.

Less than a month after the agency announced it would undertake the study, CDPHE issued a brief report saying it had found no link between the fetal abnormalities and drilling activity in Garfield County.

But CDPHE’s study had many glaring gaps. For example, the agency failed to analyze the air or water in subjects’ homes for volatile organic compounds or other hazardous contaminants emitted by drilling operations, pipelines, or storage facilities. The report looked only at the distance the subjects lived from active wells, but did not consider proximity of their homes to finished wells, leaks, spills, pipelines, storage tanks, compressors and other drilling-related facilities and equipment known to vent or leak methane and other volatile organic compounds (VOCs) into the air, water and Earth. CDPHE also failed to consider a sigificant leak of hydrocarbons into Parachute Creek, near the west end of Garfield County, that occurred in late 2012 and early 2013. In that event, an estimated 40,000 gallons of hydrocarbons evaporated into the air, and 10,000 gallons of liquid hydrocarbons spilled into Parchute Creek, which empties into the Colorado River.

The Utah Department of Health gave no indication whether their study might include the effects of ozone air pollution on pregnant mothers in the Uintah Basin, or if they intended to measure the mothers’ exposure to chemical contaminants from drilling activity, nor did they indicate when the report would be completed.